Beware: Common Mistake In Polya’s Theorem Proof And How To Avoid It

Polya’s Theorem Proof offers a powerful framework for counting distinct colorings under symmetry. However, researchers often stumble on a subtle pitfall that can derail an entire proof. In this article, we’ll identify the common mistake, explain why it happens, and show practical strategies to avoid it while keeping the reasoning clear and rigorous. Whether you’re counting colorings of a polygon, a graph, or a necklace, the same caution applies to Polya’s Theorem Proof.

Key Points

- Understand that colorings fixed by a symmetry must be constant on each cycle of that symmetry's action.

- Derive the cycle index accurately for the specific group action, rather than reusing a generic template.

- Be careful with color multiplicities and constraints; overcounting often happens when colors are not independent.

- Validate your result with small, hand-checkable cases to catch mistakes early.

- Use a systematic workflow: compute fixed colorings for each group element, then average, instead of guessing the final count.

What is the common mistake in Polya’s Theorem Proof?

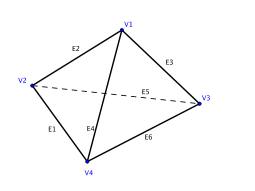

The most frequent error is confusing the action of the symmetry group on the objects with the action on the colorings themselves. It’s common to write down the cycle structure of a symmetry for the object, then assume each cycle can be colored independently. In truth, a coloring is fixed by a symmetry only if the colors are constant along each cycle in a way that respects the group action. This subtle coupling is easy to miss and leads to incorrect fixed-color counts and a wrong cycle index substitution.

Why this mistake happens

Several factors contribute: a rush to apply the formula without deriving the correct cycle index, a belief that “each cycle contributes independently,” or trying to shortcut the computation for large groups. The result is a mismatch between the actual group action on colorings and the combinatorial factors used in the cycle index.

How to avoid it

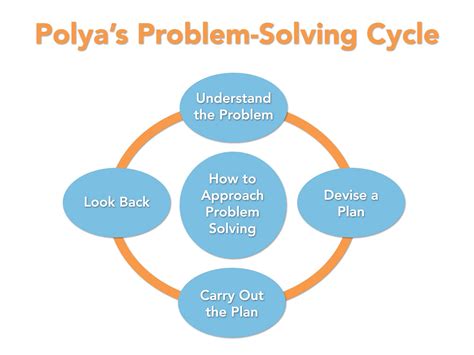

Adopt a disciplined workflow:

- Identify the true group action on the objects you are coloring and list all group elements.

- For each group element, determine its cycle decomposition on the object’s positions.

- Count the fixed colorings for that element by enforcing that each cycle is monochromatic in a way consistent with the group action.

- Assemble the cycle index and substitute the available colors carefully, then average over the group.

- Cross-check with small test cases to confirm the derived counts match direct enumeration where feasible.

What is the core misunderstanding that leads to mistakes in Polya's Theorem Proof?

+The core misunderstanding is treating the cycles of a symmetry as if colors can be assigned independently on each position. In reality, fixed colorings depend on the entire cycle structure, so you must enforce monochromatic cycles according to how the group acts.

<div class="faq-item">

<div class="faq-question">

<h3>How can I verify my Polya's Theorem Proof quickly?</h3>

<span class="faq-toggle">+</span>

</div>

<div class="faq-answer">

<p>Compute the cycle index for the specific group, perform the color substitution carefully, and compare the result with brute-force counts on small objects (like a square or a triangle) where enumeration is feasible. Consistent results boost confidence in the method.</p>

</div>

</div>

<div class="faq-item">

<div class="faq-question">

<h3>Does Polya's Theorem apply to any symmetry problem?</h3>

<span class="faq-toggle">+</span>

</div>

<div class="faq-answer">

<p>Polya's Theorem applies to colorings under a group action where the group elements permute the positions. It is especially effective for objects with well-defined symmetries, such as polygons, beads, and lattices. The key is using the correct cycle index for the given group.</p>

</div>

</div>

<div class="faq-item">

<div class="faq-question">

<h3>What is a quick sanity check after finishing the proof?</h3>

<span class="faq-toggle">+</span>

</div>

<div class="faq-answer">

<p>Test a one-color scenario and a two-color scenario on a simple object, then compare with known counts or direct enumeration. If the numbers align, the derivation is on solid ground.</p>

</div>

</div>